Maybelline Company, est. 1915

Museum Artifact: Maybelline Mascara, c. 1940s

Made By: Maybelline Co. Distr., 5900 N. Ridge Ave., Chicago, IL [Edgewater]

When the company now known as Maybelline New York marked its 100th anniversary in 2015, the celebration was—much like that patently unnecessary name change—almost suspiciously disconnected from the real history of a business born, built, and largely defined in Chicago.

A promotional blitz that could have served as the long overdue “coming out” party for Maybelline’s pioneering but little-known founder, Thomas Lyle Williams (1896-1976), was instead reduced to a few vague bits of corporate trivia.

A promotional blitz that could have served as the long overdue “coming out” party for Maybelline’s pioneering but little-known founder, Thomas Lyle Williams (1896-1976), was instead reduced to a few vague bits of corporate trivia.

“Did you know Maybel [sic] was a real person?” a writer for Fashion Week Daily reported after attending a supermodel-laden centenary gala in NYC that spring. At the same event, Maybelline’s head of marketing, Anne Marie Nelson-Bogle, regaled the audience with a three-sentence version of the corporate origin story: “Mabel was preparing dinner and had an unfortunate cooking mishap,” she said. “She singed her brows and eyelashes! So she mixed up a little coal dust and Vaseline and applied it to her lashes and brows and the first-ever mascara and brow enhancer was born.”

Mabel was, indeed, a real person—a working class Chicago girl a few years shy of women’s suffrage. And while she may or may not have actually needed the motivation of a cooking accident to start painting her face, her experiments with make-up—inside a small family home in 1915—would inspire her 19 year-old brother, Tom Lyle Williams, to build a cosmetics empire. . . . in Chicago.

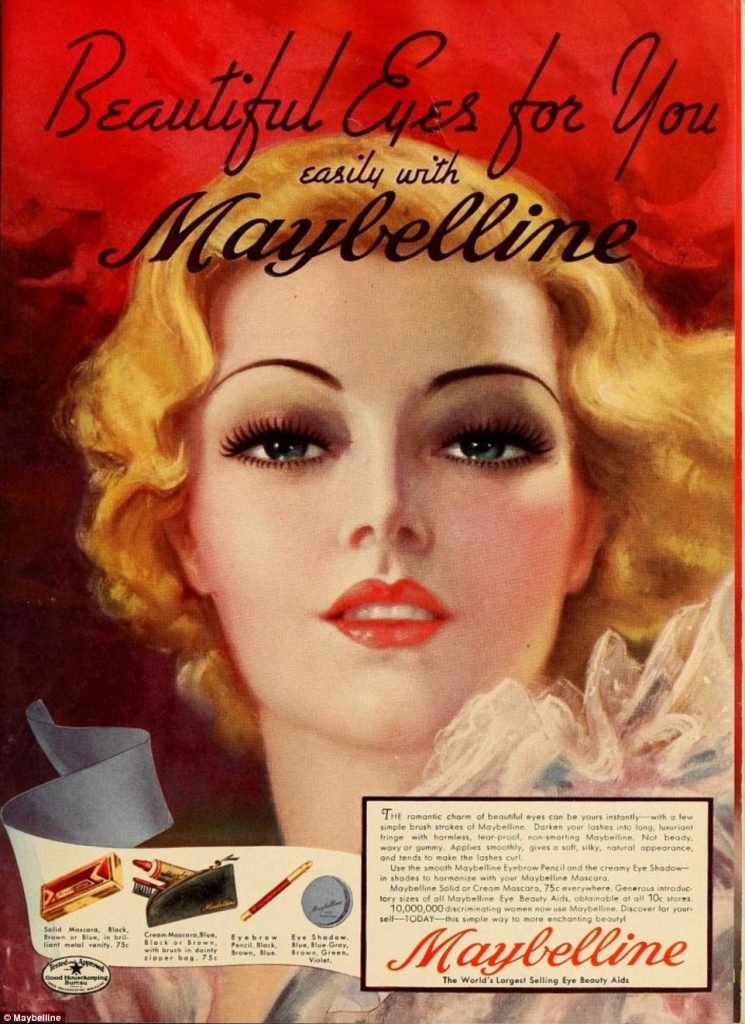

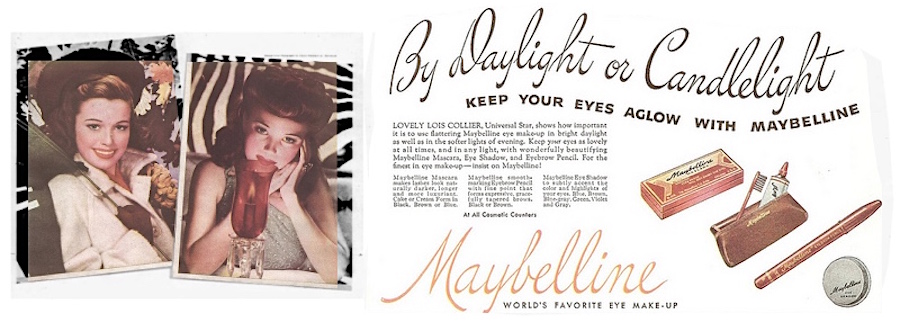

[A 1945 Maybelline ad, featuring actress Lois Collier, promoting the same small box of mascara from our museum collection. While Maybelline sold its mascara in metal vanities as early as the 1930s, our cardboard alternative was likely a product of rationing during WWII.]

[A 1945 Maybelline ad, featuring actress Lois Collier, promoting the same small box of mascara from our museum collection. While Maybelline sold its mascara in metal vanities as early as the 1930s, our cardboard alternative was likely a product of rationing during WWII.]History of Maybelline, Part I: Kid Mogul

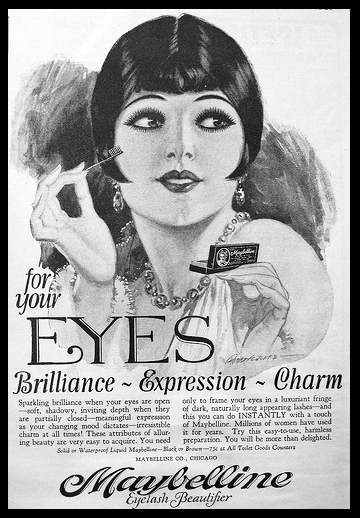

“Beautiful eyelashes and eyebrows make beautiful eyes; beautiful eyes make a beautiful face.” —advertisement for Tom Lyle Williams’ first product, Lash-Brow-Ine, c. 1918

The quote above, while not exactly poetic or electrifying ad copy, was actually a somewhat revolutionary sales pitch for its day. Eyes, of course, had been the universally agreed-upon centerpieces of aesthetic beauty for eons, but in Maybelline’s worldview, the natural shape of your eyes or the color of your iris was all quite secondary to the window dressing around them. Good make-up, Tom Lyle Williams argued, was as good as “being born with it,” as the slogan would go many decades later.

[Left: Mabel Williams, the girl who started it all. Center and Right: Early advertisements for Tom Lyle Williams’ first mail order product, Lash-Brow-Ine, which he sold under the banner of “Maybell Laboratories,” a play on his sister’s name]

[Left: Mabel Williams, the girl who started it all. Center and Right: Early advertisements for Tom Lyle Williams’ first mail order product, Lash-Brow-Ine, which he sold under the banner of “Maybell Laboratories,” a play on his sister’s name]

There have been a few different tellings over the years as to how a teenage Tom Lyle became immersed in the world of women’s make-up. Like the vast majority of gay men during his era, he lived a closeted life [Williams was married to a woman and had a child by the age of 16, before beginning what would be a life-long relationship with a man named Emery Shaver in the 1920s], so the fact that he enjoyed applying make-up to his own face—in the style of silent film stars—wasn’t exactly promoted as part of the corporate narrative. All versions of the story, though, do feature Tom getting a crash course in DIY cosmetics from his aforementioned sister Mabel—watching her apply her Vaseline / coal dust / ash concoction to her brows and eyelashes to “help them grow.”

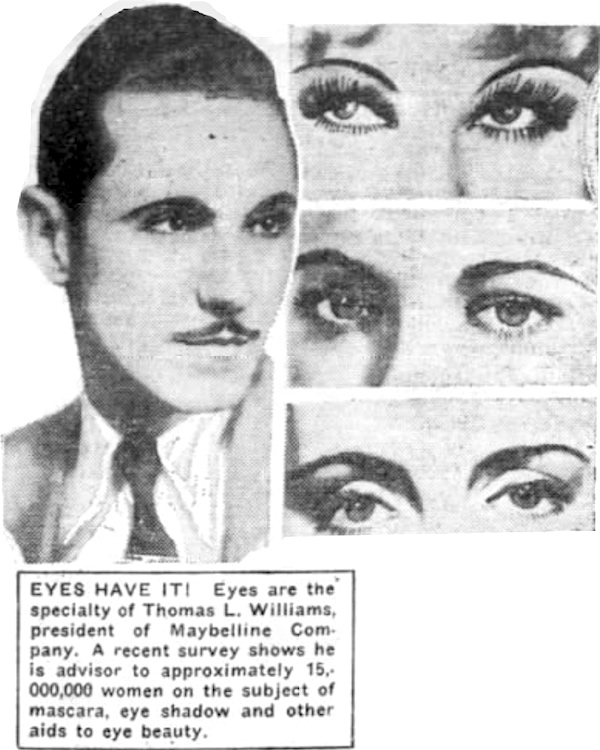

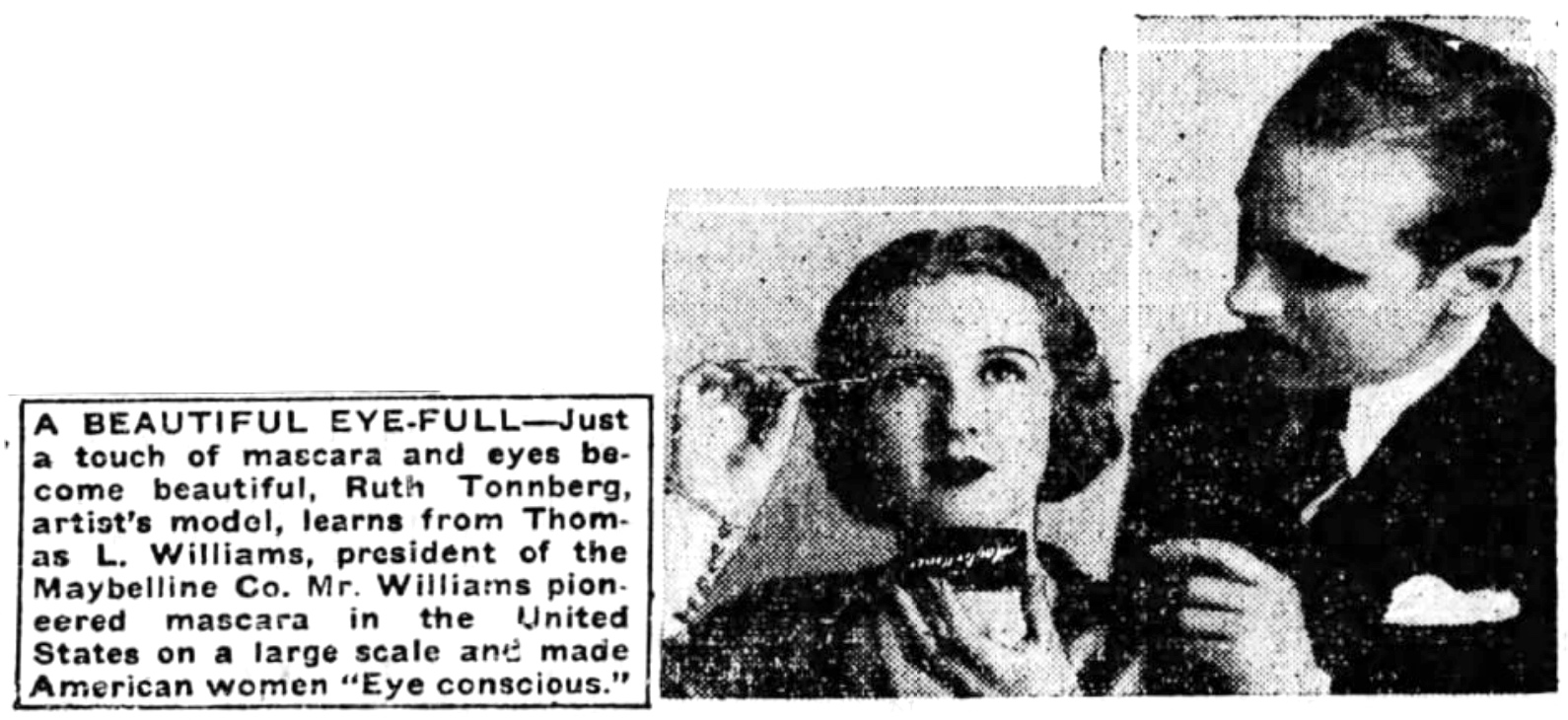

Presuming that plenty of other girls must be doing something similar in front of their vanity mirrors, Tom Lyle [pictured] found himself a chemistry set and tried adapting his sister’s formula into a more stable brand of commercial cosmetic. We could say that he “invented” modern mascara right there, but it took a while, along with some significant help from the labs of Parke, Davis & Co., an established pharmaceutical maker. Eventually, the result was Lash-Brow-Ine, a product name that intentionally played on the popularity of the Vaseline brand, much as Maybelline would a few years later.

Presuming that plenty of other girls must be doing something similar in front of their vanity mirrors, Tom Lyle [pictured] found himself a chemistry set and tried adapting his sister’s formula into a more stable brand of commercial cosmetic. We could say that he “invented” modern mascara right there, but it took a while, along with some significant help from the labs of Parke, Davis & Co., an established pharmaceutical maker. Eventually, the result was Lash-Brow-Ine, a product name that intentionally played on the popularity of the Vaseline brand, much as Maybelline would a few years later.

Tom Lyle established a small office for his new venture, “Maybell Laboratories,” at 4008 Indiana Avenue, near the Williams home at 4053 S. Prairie Avenue in Bronzeville. From there, he promoted Lash-Brow-Ine as an exclusive mail-order product, relying on a tiny ad budget to grab space in newspapers. He had a bigger obstacle than cash in the early going, however. You see, back in the 1910s, there were really only two kinds of women that society generally associated with eyelash enhancement.

“That was left to the theater and the women outside the pale of good society,” Williams delicately specified during a rare interview in 1934. “Up to comparatively recent times very few women used rouges, lipsticks, eye beautifiers and other quite obvious improvers of facial appearance. Here the real job began, because my capital was very small, and while my product was good, I was faced with the job of selling women on the idea that it was perfectly moral to use eye beautifiers.

“My job was to make women more conscious of their eyes and the possibilities of making them more alluring; to break down prejudice, and of course, to sell my product.”

[Silent film star Gloria Swanson was one of several actresses to appear in Lash-Brow-Ine advertisements, connecting the product to the glamour of the cinema]

[Silent film star Gloria Swanson was one of several actresses to appear in Lash-Brow-Ine advertisements, connecting the product to the glamour of the cinema]

The easiest avenue for making that sale, and the one that had likely inspired Mabel Williams in the first place, was the wonderful new world of moving pictures, where eyelash definition was an essential for every young star (male or female) of the silver screen. As such, Tom Williams was eventually able to recruit up-and-coming film actresses like Ethel Clayton, Viola Dana, and Gloria Swanson to appear in his ads, which were becoming ubiquitous in movie industry magazines.

“You too can have luxuriant eyebrows and long sweeping lashes by applying Lash-Brow-Ine nightly,” read a 1915 ad in Motion Picture Classic. “Thousands of society women and actresses have used this harmless and guaranteed preparation to add charm to their eyes and beauty to the face.”

Maybelline’s modern celebrity-centric marketing strategy clearly dates back to its inception, and it’s in that department where Tom Lyle Williams’ talents were best on display—first as an ambitious teenager, and later as the president and pilot of the Maybelline brand for the entirety of its 50 years in Chicago.

Maybelline’s modern celebrity-centric marketing strategy clearly dates back to its inception, and it’s in that department where Tom Lyle Williams’ talents were best on display—first as an ambitious teenager, and later as the president and pilot of the Maybelline brand for the entirety of its 50 years in Chicago.

By any measure, Williams probably ought to be one of the revered American businessmen of the 20th century—not just for his innovations and industriousness in the world of cosmetics, but for what he likely had to endure as a gay man, in a committed partnership, having to keep his personal life in the shadows to sustain his business. It’s a fascinating and potentially inspirational story, and yet, compared to the competitors who put their own names on their products—i.e., Coco Chanel, Estee Lauder, Max Factor, etc.—Williams’ legacy has continued to languish in obscurity.

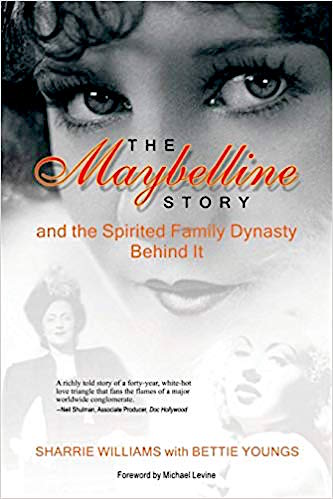

II. All in the Family

Fortunately, there is at least one in-depth resource out there covering the tale of Tom Lyle and the entire Williams clan of Chicago. Written by Tom’s own great-niece, Sharrie Williams (with Bettie Youngs), The Maybelline Story and the Spirited Family Dynasty Behind It was published in 2010. The book is far more than a simple company history, as Sharrie’s account of the family-owned business—particularly its half century of independence in Chicago—reads more like a Hollywood noir or a romance novel; rife with intrigue, in-fighting, dashing gents and fast-talking dames.

The author, Ms. Williams, was kind enough to share her insights with the Made-In-Chicago Museum, and we started by asking her about the role of Chicago itself as a character in this colorful drama.

The author, Ms. Williams, was kind enough to share her insights with the Made-In-Chicago Museum, and we started by asking her about the role of Chicago itself as a character in this colorful drama.

“Maybelline would never have exploded as it did if Tom Lyle were in another city,” she says. “After World War I, women got the vote, motion pictures were the rage, and the Jazz Age began. All of this excitement was centered in the heart of Chicago.”

Sharrie also notes that Chicago’s reputation as the heartbeat of American industry was the thing that had landed Tom Lyle there in the first place.

“Tom left the family farm in Morganfield, Kentucky, and relocated to Chicago because there was opportunity,” she says, “industry, brilliant minds, exciting people, and jobs to be had.”

Eager as Tom was to claim his own piece of that pie, however, he still relied heavily on his family to get Maybell Labs off the ground, and that dynamic would carry forward for many years to come.

“The Williams were a tight knit clan,” Sharrie says, speaking from personal experience. “Family loyalty was what Tom Lyle stood for.”

[The Williams family in 1916, from left: Tom’s brother Preston, sister Eva, Tom himself, the marvelous Ms. Mabel, brother Noel, and parents Susan and Thomas J. Williams]

[The Williams family in 1916, from left: Tom’s brother Preston, sister Eva, Tom himself, the marvelous Ms. Mabel, brother Noel, and parents Susan and Thomas J. Williams]

During the Chicago era, which stretched all the way into the late 1960s, Tom Lyle would keep Maybelline a family-owned business, operating for decades out of a central office in the Edgewater neighborhood—briefly at 4750 N. Sheridan, then the permanent location at 5900 N. Ridge Avenue. He worked at different points over the years with his siblings Noel, Preston, Mabel and Eva, along with his sisters’ husbands (the similarly named Chester Hewes and Ches Haines) and eventually his own son Tom Lyle Williams Jr., who was born back in Kentucky before Tom Sr. had figured some things out. Maybelline’s advertising man, incidentally, was Emery Shaver, Tom’s life partner. The company’s other marketing guru, Rags Ragland (hired in 1933), was the only non-family member to become an executive.

“Everyone worked together,” says Sharrie Williams, “first out of their kitchen, where they poured the original Lash-Brow-Ine into little tins at the table and carried bags of mail in wheel barrels from the train station. Later, as the Maybelline Company expanded, employees were hired. Tom Lyle’s partner, Emery Shaver, worked with him in Hollywood on Maybelline advertising, contracting the biggest Stars of the era. Tom and Emery became bi-coastal, traveling from California to Chicago, keeping an apartment on Sheridan Road. Noel J. Williams ran the Company as Vice President.”

“Everyone worked together,” says Sharrie Williams, “first out of their kitchen, where they poured the original Lash-Brow-Ine into little tins at the table and carried bags of mail in wheel barrels from the train station. Later, as the Maybelline Company expanded, employees were hired. Tom Lyle’s partner, Emery Shaver, worked with him in Hollywood on Maybelline advertising, contracting the biggest Stars of the era. Tom and Emery became bi-coastal, traveling from California to Chicago, keeping an apartment on Sheridan Road. Noel J. Williams ran the Company as Vice President.”

Sharrie Williams has admitted that not every member of her family was pleased when her book was published. While some appreciated the effort to shed light on Tom Lyle—a truly admired and beloved person within the family—others questioned the decision to share details of his personal life. Up to that point, he’d somehow remained an absolute mystery man to the outside world, to the point where Maybelline’s own Wikipedia page used to identify its founder as a “New York chemist”—wrong on both counts.

Now, thanks to Sharrie, Tom Lyle Williams’ true business savvy—as well as his potentially noteworthy place in the LGBT community’s often hidden history—are far better understood. During a time when being open about his sexuality would have spelled the end of his career, T.L. Williams found ways to survive and endure while staying true to himself.

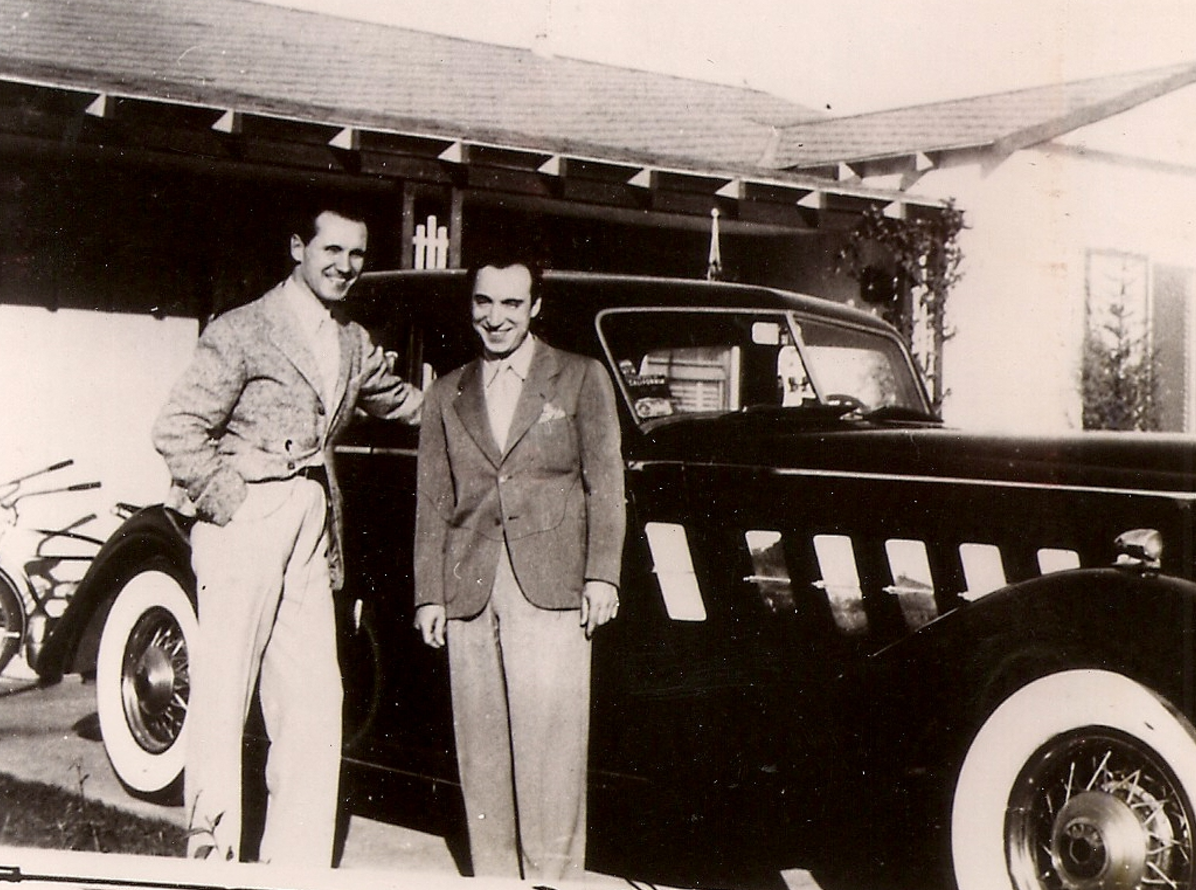

[Tom Lyle Williams with his partner of 50 years, Emery Shaver]

[Tom Lyle Williams with his partner of 50 years, Emery Shaver]

“During the 1920s, in Chicago, Tom Lyle and Emery blended into the Chicago culture,” Sharrie Williams explains. “It was a flamboyant time for young people—music, theater, movie palaces, parties, and private clubs. They didn’t stand out driving Tom Lyle’s custom-made Packards, wearing full length llama skin coats, and enhancing their features with a little Maybelline eyebrow pencil and a touch of mascara on their lashes. However, once the Great Depression hit during the 1930s, they began to stand out. They blended in far better in Hollywood. So Tom Lyle bought Rudolph Valentino’s home in the Hollywood Hills, where they cloistered themselves behind the gates to protect the Maybelline name and the family from unwanted scrutiny.”

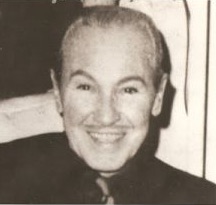

“Gays in the 1930s were not allowed to have any influence on women,” Sharrie adds, noting that the government had actual programs in place to crackdown on homosexual elements in the cosmetics industry. “It was a witch burning. The Government tried to break up the Maybelline Company by calling it a monopoly. Tom Lyle never was allowed to use his face on his products, like Max Factor or Charles Revson. Instead, he used the biggest Stars in Hollywood to represent Maybelline. Tom Lyle never let anything stop him and he never gave up believing in himself and his company. A positive thinker, he would say. ‘It’s easy to be happy when things are going your way, the true test of character is staying positive during the hard times.’” [picture below: Tom Lyle Williams in 1934]

III. The “M” on Ridge Avenue

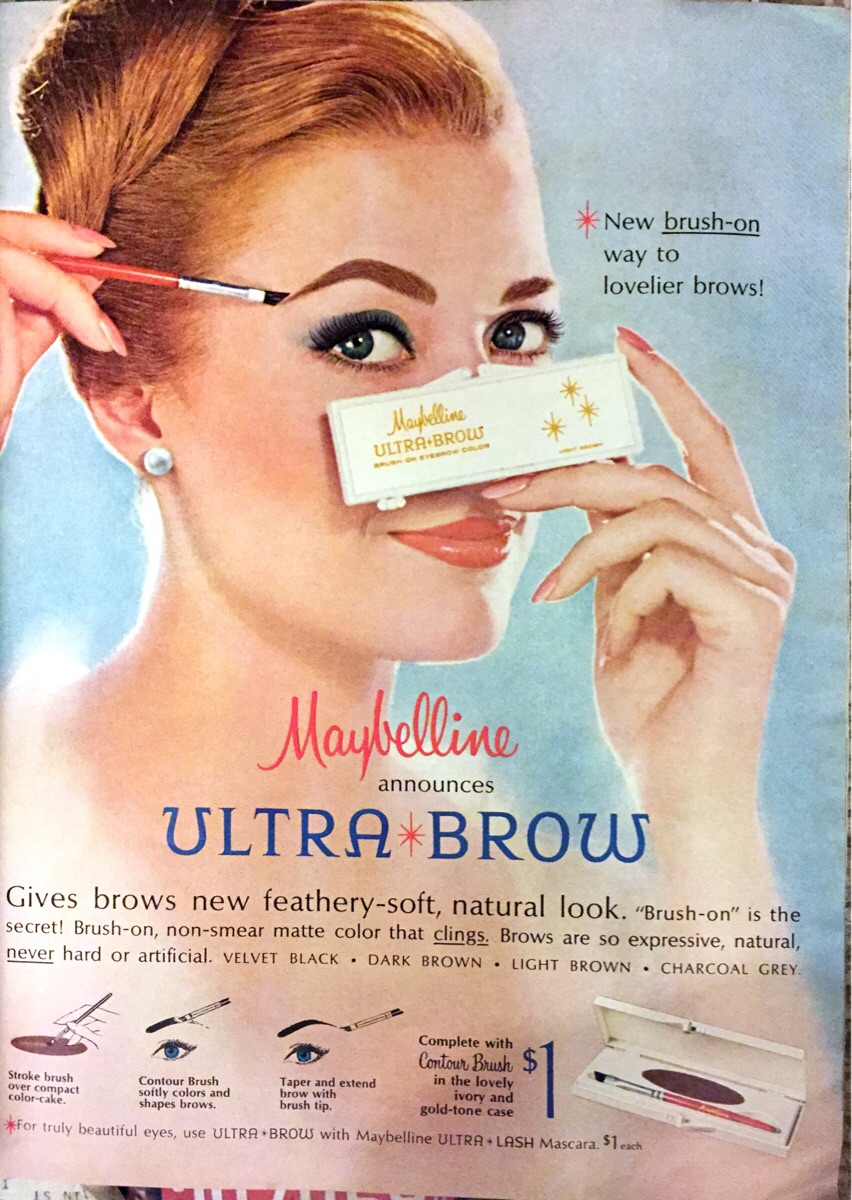

Maybelline faced no shortage of bumps in the road during its first few decades, but they generally zigged successfully when others zagged, using innovative strategies in both product development and promotions. During the Depression, the company added eyeshadow, pencil, and an eyelash grower to its growing line of cosmetics, along with the miniature style of mascara boxes like the one in our museum collection.

“It was a smaller version of the original 75-cent box of mascara,” Sharrie Williams says. “The new Depression size sold for 10 cents.”

[First introduced in the ’30s, the version of Maybelline brown mascara in our museum collection likely dates from around 1945. Unlike modern mascara brushes, this design was more like a miniature toothrbrush, which probably wasn’t ideal for precision.]

[First introduced in the ’30s, the version of Maybelline brown mascara in our museum collection likely dates from around 1945. Unlike modern mascara brushes, this design was more like a miniature toothrbrush, which probably wasn’t ideal for precision.]

“Tom Lyle took Maybelline out of the classifieds and put it into dime stores,” Sharrie ads, “so the average American girl could have easy access and it was affordable. He found that women would rather spend their dimes on his cosmetics than buy food for the table. It’s still that way today. During economic downturns, cosmetic sales go up while other products go down. Women have to have their beautiful eyes no matter what.”

[1934 Maybelline ad featuring the “Before & After” effect and Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval]

[1934 Maybelline ad featuring the “Before & After” effect and Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval]

Among the other cosmetic industry standards that Maybelline helped launch:

♦ Before & After advertisements showcasing glamorous transformations

♦ First cosmetics company to do radio advertising

♦ “Carded Merchandising,” developed by the marketing genius Rags Ragland, showcased the little red Maybelline boxes in an upright display rather than stacked in a pile on the counter

♦ Film Star Faces – From the flappers of the silent film era to the likes of Joan Crawford and Betty Grable in the 1940s, Maybelline was all Hollywood from the get-go

♦ Using the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval to communicate “trust, purity and perfection”

♦ Before & After advertisements showcasing glamorous transformations

♦ First cosmetics company to do radio advertising

♦ “Carded Merchandising,” developed by the marketing genius Rags Ragland, showcased the little red Maybelline boxes in an upright display rather than stacked in a pile on the counter

♦ Film Star Faces – From the flappers of the silent film era to the likes of Joan Crawford and Betty Grable in the 1940s, Maybelline was all Hollywood from the get-go

♦ Using the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval to communicate “trust, purity and perfection”

Persisting through the Depression and World War II, Maybelline was the international name in brow and lash cosmetics, fending off dozens of imitators. Tom Lyle Williams, now in semi-retirement, was spending the majority of his time in L.A. by the 1950s. Nonetheless, the company headquarters remained in Chicago at 5900 N. Ridge Ave., where constant expansion increased the workforce from just 30 in 1953 to likely at least twice that figure by the 1960s.

Persisting through the Depression and World War II, Maybelline was the international name in brow and lash cosmetics, fending off dozens of imitators. Tom Lyle Williams, now in semi-retirement, was spending the majority of his time in L.A. by the 1950s. Nonetheless, the company headquarters remained in Chicago at 5900 N. Ridge Ave., where constant expansion increased the workforce from just 30 in 1953 to likely at least twice that figure by the 1960s.

All these decades later, that building still has the familiar Maybelline “M” carved above the doorway; well preserved, but almost entirely unnoticed by the average passerby. It’s understandable, I suppose. In most other respects, the old complex is a pretty nondescript three-story affair—but its inner workings back in the ’50s and ’60s are still quite vivid to Sharrie Williams, who used to visit the family business in her youth.

“It was a handsome building, but nothing unusual,” she says. “Entering at the company entrance at 5900 North Ridge Avenue, there was a main-floor foyer with a terrazzo floor and paneled walls. A semi-circular stair with curved brass rail rose out of sight to a second-floor office and reception area. Behind the receptionist window was a general office area where about a dozen people worked. Opposite the receptionist was a door leading to a group of four executive offices.

“Back to the lower-level foyer, another door led to the main-floor operating areas. First, the Traffic and Shipping Departments were in adjoining spaces, convenient to a “dumb-waiter” device that dropped orders from the general office above to the lower area. Further into the plant, the ‘Assembly Room’ came along, where maybe 50 ladies at individual work desks assembled thousands of packages of Maybelline products by hand daily. The room was set up with a supervisor’s desk in front, with assemblers in rows across the room, similar to a school classroom or study hall. Hazel Peterson, the supervisor, stopped any chit-chat if it got anywhere near disruptive.”

[Maybelline’s former Ridge Avenue offices, circa 1932 (above) and 2017 (below)]

“In addition to the Assembly Room, machine packaging was beginning to emerge. There were two smaller rooms, former retail store spaces, that were set up to produce this new packaging. One room packaged the medium-sized cake and cream mascaras and pencils onto gold cards, putting them first into blisters or ‘bubbles,’ then stapling them to the card.

“The second store-front room contained a machine that sealed products in blisters to cards by a dielectric sealing process. Several newer products went to market from this room, including the ‘Brush ‘N Comb,’ automatic self-sharpening pencil and refill, and the brand new liquid ‘Magic Mascara’ and refill. The latter was proving to be a smash hit in the marketplace, and we were still running behind to keep pace with demand when I started.”

Sharrie also remembers just one docking station for all shipping and receiving by truck, and one freight elevator, which led to a warehouse and storage area.

Sharrie also remembers just one docking station for all shipping and receiving by truck, and one freight elevator, which led to a warehouse and storage area.

“And that was the Maybelline footprint,” she says, “part of three levels of the building. Also, there was a line of active retail store space along the Clark Street frontage. A Rexall drug store occupied the point of the building, wrapping around to the Ridge Avenue frontage. Also, in no order, there was a barber shop, a short-order restaurant, an ice cream store, a hardware store, and finally a currency exchange.

“Elsewhere, there were several dozen apartments on the upper two floors of the building. Many of the residents were also Maybelline employees, so they only had to go downstairs to go to work!”

The company was still in Edgewater in the mid ‘60s and doing well, but the death of Tom Lyle’s partner Emery Shaver in 1964 set the wheels in motion for major changes.

IV. Broken Promises

“Tom Lyle [pictured] was now 70, and was not well,” says Sharrie Williams. “The loss of his partner was devastating. He began looking for a buyer.”

“Tom Lyle [pictured] was now 70, and was not well,” says Sharrie Williams. “The loss of his partner was devastating. He began looking for a buyer.”

In 1967, Plough Inc. dropped a $136 million bid in cash and stock (about a billion dollars in today’s money), and just like that, the Williams family surrendered its control of the company they’d built.

“Tom Lyle had incorporated Maybelline in 1954,” Sharrie says, “but the stock was only divided among the family and the employees who had been loyal to Maybelline since the beginning. Even the stock boy received one million dollars. A large portion was given to The Goodwill and CARE.”

Initially, the bittersweet emotions around Maybelline’s sale were eased by promises from Abe Plough that the company would remain in Chicago. It was only when that promise went swiftly out the window that the elderly Tom Lyle came to regret things.

“He regretted that he hadn’t groomed the younger generation to take over the company,” says Sharrie Williams [pictured below]. “He was heartbroken. . . The employees that were promised that their jobs would remain in Chicago were given letters of dismissal. It was painful for Tom Lyle to see his baby now being run without him at the helm.”

Plough initially relocated the business to his own home turf in Memphis, and manufacturing was set up several years later in Little Rock, Arkansas, where much of it still remains.

Plough initially relocated the business to his own home turf in Memphis, and manufacturing was set up several years later in Little Rock, Arkansas, where much of it still remains.

Today’s version of Maybelline is owned by L’Oreal and based, of course, in New York [Brooklyn, to be specific]. Long since severed from any connection to the Williams family, the company pays little homage to its early history, whether its an anniversary year or just an “About” page on their website. Every facet of its marketing and operation, however, still owes a debt to those slightly more humble beginnings.

“You can take the company out of Chicago, but you can’t take Chicago out of its roots,” Sharrie Williams says. “You can’t take the history out of the name.”

We certainly encourage you to check out Sharrie Williams’ book The Maybelline Story and her related, regularly updated website at http://www.maybellinebook.com/

[1950s Maybelline TV advertisement]

[A pair of early Lash-Brow-Ine ads starring Gloria Swanson]

[A pair of early Lash-Brow-Ine ads starring Gloria Swanson] [1940 ad starring Betty Grable, who kind of resembles Jennifer Lawrence in this one]

[1940 ad starring Betty Grable, who kind of resembles Jennifer Lawrence in this one] [Above and below: Maybelline ads from the Sunday Comics section of newspapers in 1940 didn’t exactly scream “women’s lib.” The storylines of “Sis Takes a Hand” and “From Office to Altar” both use Maybelline products as a bridge to help women snare a husband; the end-all-be-all motivator for the mid-century single lady.]

[Above and below: Maybelline ads from the Sunday Comics section of newspapers in 1940 didn’t exactly scream “women’s lib.” The storylines of “Sis Takes a Hand” and “From Office to Altar” both use Maybelline products as a bridge to help women snare a husband; the end-all-be-all motivator for the mid-century single lady.]

Sources:

The Maybelline Story, by Sharrie Williams w/ Bettie Youngs

“Newspaper Advertising Does Pay” – The Times (Munster, IN), Jan 4, 1934

“Maybelline New York Celebrates Its 100th Anniversary” – Fashion Week Daily, May 15, 2015

Archived Reader Comments:

“I remembered that the company moved to Alsip before it went South. And it was a cousin of mine that owned the ice cream store on the Clark side of the building. She was really mad when they forced her out in the 50s for expansion. I also remember the huge “M”s painted on every storefront window on both Clark & Ridge in the same style as the stone one over the entrance.” —Becca, 2019

“What a fabulous story! I remember using the Ultra-Brow back when, and my mother used the little red plastic box. Never knew the history of it, and am pleasantly surprised. Hope to see the display sometime.  ” —CPL, 2018

” —CPL, 2018

” —CPL, 2018

” —CPL, 2018

No comments:

Post a Comment